The internet (part 4 of 4): Wrap-up — The internet paved the path for a brighter future.

- Cosmo Mwamwembe

- Mar 12, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: Feb 5, 2024

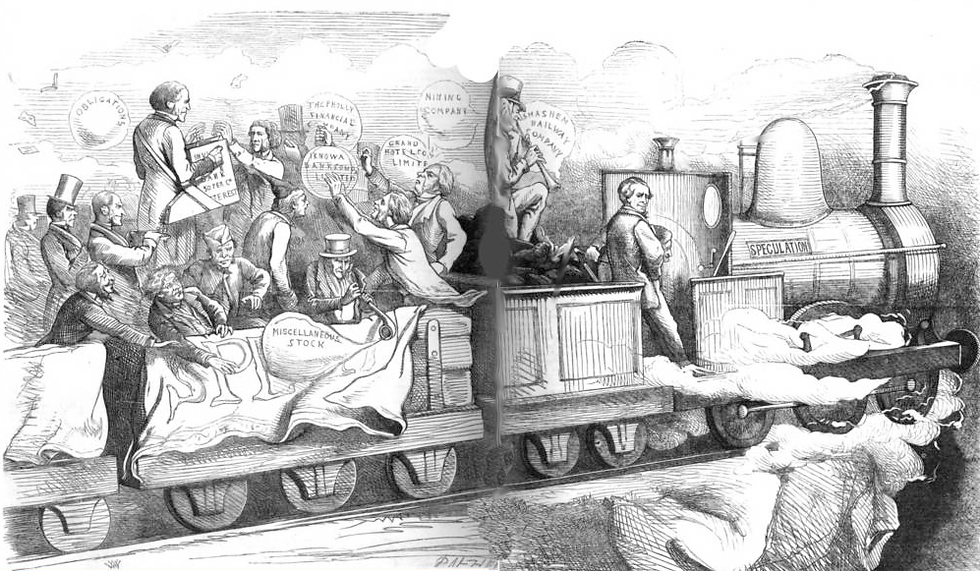

The dot-com bubble was more like Railway Mania than any previous bubble.

The dot-com bubble was unique in many ways. But, if we were to compare it to other bubbles, the closest comparable would be the British Railway Mania of the 19th century.

Around the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the 1830s and 1850s, when the UK was becoming the world’s manufacturing powerhouse, railroads emerged as the new grandiose thing to catalyse the new revolution. It promised bulky, cheaper, and faster transportation of goods and people. Like the internet, the idea was initially ridiculed, and many thought canals and wagons were enough. But soon railroads became mainstream, and investing in them was very lucrative, especially after excessive gains from early companies. Railroad stocks exploded and made London the leading stock exchange in the world.

Exaggerated newspaper advertisements and lofty projections fuelled the euphoria. The buzz swept up even popular names like Charles Darwin, the father of natural selection. At peak, railroad investments are estimated to have accounted for around 7% of UK GDP—half of the country's investments.

Innovation-driven bubbles are [often] essential pain for new paradigm shift

The aftermath of the railway mania resulted in negative stories that persist today, but the innovation and investments created the backbone of the British infrastructure that would accelerate the Industrial Revolution. Over 6,000 miles of new rail network were built during the period.

This is similar to the dot-com. Yes, the bubble burst and money was lost, but those businesses built the foundation and infrastructure for the world we live in today. Few early companies like Amazon, Yahoo!, eBay and Google that managed to build strong businesses outside the hype [and with luck] not only survived but thrived in the next few years. And many business ideas that failed would also reincarnate with different names few years later. We are now familiar with names like chewy.com, an online retailer of pet food and other products founded in 2011, or Instacart, a grocery delivery and pick-up service company founded in 2012. But these are replicas of pets.com and Webvan (part 3), with a difference being that they are operating in a more mature market with better infrastructure (warehouses, internet speed, internet penetration, secure payment systems).

Business of the people, for the people, and by the people

From the beginning of the ancient entrepreneurship in New Guinea to early agriculture, invention of money, creation of markets and the industrial revolution, we, humans, have always strived to make tomorrow better than today. Not just for ourselves, but our communities too. We have made tools, built cities, and found cures for diseases. This pursuit for efficiency, convenience [and a little bit of pleasure -:) was even more pronounced than ever during the internet era—partly because of the instantaneous feedback system the internet provided. Internet companies promised to deliver just that, at no extra cost or effort for consumers. Amazon and eBay responded in e-commerce. Google would too with search. Netscape had brought people and businesses online but google offered to “organise the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful” in 1998.

In the media industry, Napster (not Netscape in part 1) is the best example of a company that saw the future and understood the importance of giving people “what they want, when they want it, how they want it” *. The company marked the emergence of decentralised peer-to-peer (P2P) music sharing by enabling users to download mp3 files from each other's hard-drives over the internet. Shortly, the platform would amass 25-80 million users. But, as with most dot-com companies, first-mover advantage didn't work for Napster. Music industry titans chocked the company with unending lawsuits until shutting down in 2002. However, Napster's short-lived success poked a hole in the notorious music industry and paved way for many companies, including Apple, Spotify, Facebook, YouTube. Unfortunately for them, timing mostly beats product.

Accelerating change: The present was yesterday, and the future is here

The internet is a medium, an enabler, and a gateway to the world of abundance. Through it, thousands of amazing products and services have emerged over the past few decades, transforming every industry, and streamlining processes.

When you look at the history of innovation, you'll realise that the timeline for technology development and adoption has continued to shrink rapidly. Since the advent of the internet in the 1990s, this shrinkage has been accelerated.

Within a brief time, the number of people online has surged from 0.5% in 1990 to 7% by the time the dot-com bubble burst (50% in the US). Today, about 64% (5.16 billion) of the world is connected. This is a massive achievement, albeit unequally distributed.

"If you went to bed last night as an industrial company, you’re going to wake up this morning as a software and analytics company.”

Jeff Immelt, former CEO of General Electric

Thinking of the future is even more exciting because it feels like it's already here. Paraphrasing Max Roser's words (The World in Data), most of us today are lucky because, unlike our grandparents who lived to witness a single technological change or none, we have a chance to see multiple unimaginable changes in our lifetime. I am particularly curious about AI, which I think is likely to be the X factor among the many brilliant technologies being developed. And I think that the recent hype around certain major milestones with AI, such as humanoid robots and ChatGPT, are mainly catalysts for adoption and to draw attention of business decision makers. The true impact of AI is more subtle. It's the AI embedded in key products and services we use every day, translating into efficiency, productivity, customer engagements etc. I also believe that disruptive innovations are inevitable when the time is right (part 3), and this decade seems like a prime time.

What about the widening inequality gap?

I wish I had an answer. As mentioned above, about 64% of the world is connected today, with wide disparities between developed and developing countries. However, developing nations have shown the fastest internet penetration and many alternative technologies since around 2010.

Whether developing countries will catch up [soon] is open for debate. The IDC and Red Hat 2022 research estimates that Sub Sahara Africa for example is about 5 years behind in the deployment of emerging technologies like AI. For technologies that feed on each other, get better with time, and have exponential growth, it is difficult to imagine inequality gap narrowing soon when some parts of the world are years behind. However, innovative technologies also make the world much more accessible and present uniquely infinite opportunities. Let me know what you think.

* Brian McCullough's book "How the Internet Happened: From Netscape to the iPhone". This was my main inspiration for these episodes, along with "The Hard Thing About Hard Things" by Ben Horowitz.

Comments